. . . Measure your future life in twenty-year potentialities. Your second twenty years(³) is when you refine yourself and make yourself better at what you've begun. Your third twenty years is when you either rebuild yourself from your mistakes, continue to make bigger mistakes, or strive to teach yourself how to set, and efficiently accomplish, harder goals. Your last twenty years is for teaching others what you learned and preparing your happy-content self for the inevitable aging and death.

When writing this footnote in a letter to Dre, I realized-as-each finger tapped out the next word, I was giving myself a snapshot of advice. Advice based on myself. My self. The portion of me who is not ego.

The first time I recall realizing that part of me existed was when I came out of a daydream. It feels in my memory that the sun on my face had caused my eyes to shut rather than continue to squint down the slope of the hill against the harsh sun at my squealing and chattering classmates. I dreamed, but not completely without intention. The dream's content was apparently unimportant, even then. The purpose—everyone is trying to make themselves smile at recess—is this, this is something I can do for me. Us. For us. To myself.

The basis of these ideas, at the time, were sprouting from the collective classmates (which included me) coming to terms with the phrase "me, myself, and I"—imagined inward about a place where someone could feel relaxed and comfortable and warm (without having to chase or be chased, tether-ball or swings, tease or be teased). I finished the daydream as the bell rung us in. I drifted back to my seat in contentment.

I know that I daydreamed before then, because the daydream was not an unfamiliar act; but this specific daydream handed me a key. The first part of "me, myself, and I" was the part who sat by myself at recess. The last part of "me, myself, and I" was the drive to listen inside, because I'm no different than that horde (which definitely includes those down there who are so obviously pretending to teach).

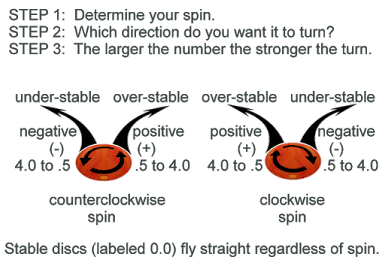

The key. It was the ability to remember. Remember that daydreaming exists on my "things available to do today" list. If you like to play disc golf, but never go anymore; maybe it is simply because you have taken it off your list. If you want to play disc golf, set out your discs! Remind yourself. Maybe you should look at your mental key-ring and see if you like playing or if you "liked" playing.

There are things that part of "me, myself, and I" once did habitually for pleasure-based-reasons but that part of myself only exists in memories. I chose to remove that key from my key-ring. Maybe because I am only capable of comfortably carring a specific number of keys in my mental pocket. Or (also, maybe) I do not want to carry more than a certain number of keys because increasing the size of my key-ring does not result in an increase in the number of hours in my day.

I've never taken the daydream-key off. Not since I got it in fifth grade.

Which was when I began second twenty years-ing (not "adulting" yet, at 10). But that definitely was me starting to "refine myself and make myself better." My third twenty years did not begin until I retired from the military (at 43). Occasionally, it feels like I've already begun my fourth twenty years; but this me (now 64) I know that, forest-for-the-trees, I am unsure this is accurate. Maybe I'm still rebuilding. It certainly seems accomplishing harder goals with more efficiency is going on in the background as well as the foreground.

rabbit-hole-ing: