What is the cement of memory?

Does what we remember form who we are?

Why do we forget 99% of our lives?

As I typed this opening

paragraph

in 2019, my brain was switching between thoughts about choosing interesting

words that would entertain itself as it compiled this sentence and—

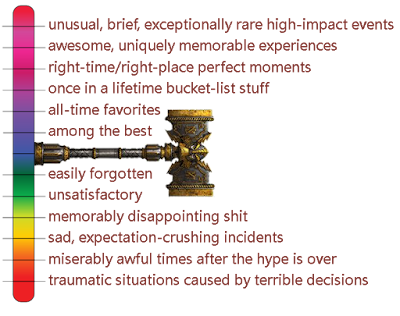

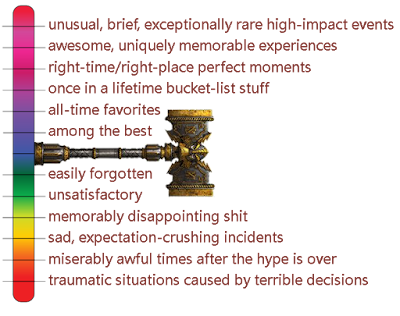

switch—scrounged thru my memory-attic for events which might fit in a bright mauve

container labelled ‘

overwhelming’. My as-I-typed brain then decided that the first event to go in was

Witnessing—for almost two full minutes—the

2017 total eclipse of the sun. I had prepared for that event for months. I'd bought expensive wrap-around viewing glasses and a phone-app to track

where the shadow was going to be. Weeks earlier, I'd driven a few hundred

miles to reconnoiter and read articles describing what to look for when

it happened. The day of, I had woke at 4am for a 5am departure in order to

set-up three hours ahead of time and as the moon began to creep across the

sun, I recalled aloud (for the handful of people with me) memories of a few previous

partial eclipses and I used the term

underwhelming to describe those

curled and faded snapshots.—

switch—Those vague recollections of pinholes in paper and flimsy cardboard glasses

were now attached—like a deflated balloon static-stuck to the back of a

worn-out child’s sweater—to this 2017 overwhelming event. (I typed

‘overshadowing event’ and edited it so as to not end this paragraph on a

pun.)—

switch—

The moment when the entire moon’s

shadow—

the umbra—completely covered the sun: the blue sky turned

black; the yellow corona around the sun became white; stars became visible; the

air temperature dropped; the silence of no-more bird and insect noises grabbed

for my attention; spots of corona-sunlight, inside of darker shadows, took-on

the changing shape (circular to crescent) of the umbra; and ripples of light

wavered across the ground like faint “light snakes.” My senses were

overloaded. My brain could not catch up. There was no time to think or

focus.

—

switch—It seems that my as-I-type brain considers it to be desirable when it-itself is

unable to function as it normally functions (which, it considers to be

its norm; its steady-state; its comfortable, uneventful, default mode; its

regular state of being, which is

neither over- nor under-whelmed) and this asItype brain is not putting anything into

its memory. Short-term memory disappears unless something over- or

under-whelms enough to get stored long-term.

I know if I were not currently documenting my thoughts—an act which facilitates asItype to be able, in the future, to

become asIread (which, in turn, will become the me that has re-remembered

based on what that previous-me wrote)—I would, very soon, no longer be able to

recall how I occupied myself this 2019 mid-November Friday morning. If I'd

instead been studying, reading, hiking, gaming, painting, listening to music,

watching videos, talking with friends, playing with my cat, or performing

routine chores, I would (probably) not be able to answer the question, “

What did you do?” Because of these words, these paragraphs, this essay (about normally

neither being over- or under-whelmed) I can say I was writing an essay about

memory.

Now, asItype wonders why are our

recollections valued? Is being able to recall something because it was

sufficiently overwhelming/underwhelming to become immediately-permanently

locked in long-term memory a prerequisite to being consciously aware of what

is important to who we are and who we want to be? And—

switch—let me dig for a stronger, more recent, memory to stick in the intense

yellow

underwhelming container (next to those partial eclipses).

Earlier in 2019, I drove through Glacier National Park. I would not use

the word

boring to describe the slow procession up and over—but I would

not use the word

exciting either. Rivulets of snow melt soaked me

a few times (cabriolet top was down) and some of the hairpin turns with sheer

drops revealed very interesting views; but a complete lack of wildlife and

over 90 minutes of traffic-jams combined to make the 50-mile drive an

unsatisfactory experience.—

switch—

Why?—my asItype-self

asks itself. What made this 2019 drive memorably

underwhelming?

One answer is that my preconceived

expectations were unmet; during my first visit to Glacier National Park (in 2006) the Going-To-The-Sun Road was closed because of snow (which

created—in that 2006-me’s brain—an unfulfilled desire). On that trip, I

felt privileged-lucky to see (and was slightly overwhelmed seeing): bald eagle, elk, black bears and grizzly

bears, and experienced no vehicle traffic or full parking lots.